I like to write sometimes, but for ninety nine hours out of a hundred I’m not in the mood. I supposedly like to read as well, but also need to be in the mood. The parameters of what I find myself capable of reading with good attention are painfully slim, I find almost everything incredibly boring to read. But after I’ve finally read something I like, it often gets me in the mood to try to write about something – to attempt to reproduce a piece of work of passable literary quality transcribed into a subject on which I could be considered authoritative and hold enough experience in to have the justifiable nerve to write about. The bottleneck comes therefore as a trifecta; topics I find interesting enough to read about constantly elude me, so I read less; reading less means I am more seldom in the mood to write; and there is in this world merely one subject matter on which I would consider myself well-versed enough to at least be able to provide more than a dozen thousand words of up-to-mark insight.

The subject is, rather embarrassingly, what amounts to sneaking into places I’m not meant to be in, and as such, that others do not get the chance to see. The font of fad has christened this thing, this activity, as urban exploring. Let’s save some time and call it UE while we can. Indeed, UE is one of the twenty-first century’s fastest growing crazes, centred around taking various levels of deviant risk in the hope of achieving a tailored dose of instantaneous and novel reward. Whilst there are as many different definitions of it as there are different demographics which partake in it, this one probably covers all the bases best: “travelling on foot, usually trespassing on private or sensitive land, into parts of the man-made environment which can be classed as ‘ROADS’ (Restricted, Obsolete, Abandoned or Derelict Spaces), as a leisure activity.”

The first two things to know about UE is, one, that it is terrifically easy, and two, that it doesn’t really know what it is. It is not an art, a skill, and it is definitely not – as some who do it have referred to it as – a ‘sport’. If you were to ask somebody who has never set foot on a skateboard before, for example, to follow a professional skateboarder around a supermarket car park and attempt to repeat each arrangement of flips and rotations they make the board do with their feet, the novice would not even be able to stand on the thing and move around, let alone attempt copying the tricks, which would require hundreds, thousands of hours of repetitive failure, honing and muscle memory-building to be able to do. If you were to ask someone of average physical ability to follow an ‘urban explorer’ into an abandoned building – through some bushes, over a piece of Heras, through a broken ground floor window – and proceed to take photographs of it with a DSLR camera they have bought charged and ready from an electronics shop, I would be concerned for their wider wellbeing vis-a-vis the toils of everyday life if they were to struggle with any of the demands of this task. If physically able to do at least one pull-up and read a map on a smartphone, one has unlocked the physical and mental capacity to partake in ninety-nine percent of what the scope of UE requires. No ten thousand hours, no practice exercise.

Nor is UE a snug fit into the world of formal thinking; that of the historian, the sociologist, the geographer or the archaeologist. Despite best intended efforts to cite themes from ‘autoethnographic immersion’ in the ‘lost spaces of cities’ to the ‘olfactory stimulation of derelict buildings’, a feature in Nature remains far-fetched. A piece in the Oxford Journal of Social History is equally. It just does not conform, does not help anyone, further anything, tick the right boxes – so says the professor of traditional disciplines. Upon its high horse, academia giggles pitifully at the student as he tries to plough his own furrow, his eyes abeam as he brings his Harvard referenced essay on ‘retaking ownership of the lost urban environment’ or ‘alternative field work into the architectural details of mid-century modernism’ to the seminar.

Nor does it infer some sort of commercial venture. Avenues to make a living which heavily involve the bulk of one’s experiential role being one’s passion project are mostly confined to advertisement and/or branding revenues from large social media followings, or by venturing into the nonsensical world of the art marketplace. Media content that involves “travelling on foot into parts of the man-made environment which can be classed as ROADS as a leisure activity” rarely amasses the numbers required for serious celebration, whilst the market for expensive prints of photographs themed on and procured by UE and its subject matter has but room for infinitesimal participants. For a commercially driven urban explorer, styles of media content which have been proven to produce any notable pocket money are further limited to either filming oneself talking into a camera whilst walking around somewhere, or filming oneself doing daredevil antics using the man-made environment to this end. These two styles aptly derive from two rather older professions: the television presenter and the stuntman. Both in turn fall under the umbrella of the even more antiquated line of work of the clown or court jester. Go figure.

It is then nothing more than a lowly hobby. One can draw the most comparisons to stamp collecting. An urban explorer will over time and repeated practice of the activity amass a portfolio of photographic matter proving visits to and documenting details of numerous artificial localities which the non-urban explorer does not get the opportunity to travel to. Some stampbooks are more impressive than others; full of a larger number of stamps, containing stamps of historical significance, stamps of a noteworthy aesthetic, rarer stamps – some of which by context indicating that special lengths most other collectors are unwilling or unable to go to were involved in their acquisition. Some stamp collectors get jealous of others’ collections, some don’t. If a stamp collector just collects the stamps that are on letters they receive on their front porch, their stamp collection might not be terribly varied, but it will however have not cost them any money or required much effort. An urban explorer who ventures into the same few abandoned buildings within walking distance of their local area and nothing further will also amass a very homogeneous portfolio, but will have undertaken the hobby gratuitously, at little exertion. For both the stamp collector and the urban explorer to acquire a diversified portfolio there must be an investment; be it time spent scouring the internet and monitoring item market price or the physical effort of infiltration and the price of a full tank of petrol many times over. The inputs are all about lengths of pursuit, the positive outputs all about the collectable item.

In UE, the collectable items are places: ROADS. Whilst inputs concern overcoming a range of obstacles, it’s all about places at the end of the day. They’re the stars of the show, what really matters. The name of the game. Different places; their distinctions, stories, attributes, currencies, soul – but places not of any traditional reverence. Quite the contrary. It all pivots around a phenomenon that human emotion toward the idea of the conventionally beautiful artificial space has been warped so extensively in the last half a century that today people are growing bored of the world around them.

A few generations ago, it was all inverse. All emphasis and excitement was on progress: the next big thing. On reaching heights not yet conquered, painting the complete, glistening picture of the world, on a vision of striving toward realising a future dominated by the artificial which only existed in the imagination. What was next to create, to accomplish, build – that was what was on the tip of everyone’s tongues. Everest is there – all the rage is when will it be scaled? We know this ancient civilisation existed because it’s alluded to in recovered scriptures, when will their temples be dug up? We know nothing of the great desert on the Arabian peninsula, when will Wilfred Thesiger cross it and write about what it’s like? The flying cars and mile-high skyscrapers of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and other popular science fiction – when will they become reality, when will we invent them, build them? The finished map of the world and the manifestation of man-made ambition had yet to be scratched up to an acceptable standard against the hype. There was still much to do, so nothing was forgotten; everywhere already touchable was of a relevance, and everything that was up next held a mystique. People couldn’t travel far, the distant parts of the world were so much less reachable, the idea of skyscrapers of glass so idealistic; so everywhere else and everywhere yet to come was what was aspirational – was what was exotic. The everyday local, contrarily, was prosaic; the length and breadth of what most peoples’ lives could ever sum to.

Then in the space of a few decades: satellites, satellite imagery, and eventually the whole photographic map of the world from above in minute detail as we know it. Everywhere had eyes on it. Along with it came the jet age, mass commercial tourism for all, every spot on the planet less than twenty four hours’ journey unless you’re off to Pitcairn Island, and big cityscapes of glass and marble for every business district of every capital. For the contemporary young demographic the concept of the exotic which their parents and grandparents knew started to dilute; formerly distant lands and mysterious cultures were integrated into everyday media, the map of the world held no surprises to anyone, and something out of Metropolis had sprouted up in the space of ten years in what Wilfred Thesiger’s coevals knew as the ‘Empty Quarter’ – in hideous taste at that. As if suddenly, nothing was unknown any more. Nothing was novel, and little was tasteful. To top it off, the future of natural discovery and technological advancement alike was no longer exciting; it was frightening, anxiety-inducing. Full of doom and gloom, demise, collapse. Now, everything was prosaic. So where could possibly be exotic?

Celebrated Harvard cultural theorist Svetlana Boym was on to something when she declared that “the twentieth century began with a futuristic utopia, and ended with nostalgia.” It was not an awfully long time in the grand scheme before eventually a new generation decided that instead of a glistening, idealised future, rather: they pined for the nostalgic artificial. In the early 2020s, a piece of horror-themed audiovisual artwork called The Backrooms emerged to find widespread popularity amongst a young online audience. Any reader born in the nineties or later will be familiar. The Backrooms will probably come to be a source of confusion for art historians; neither abstract nor impressionistic, provocative nor extravagant. The Backrooms at its most elementary is a virtually-rendered never-ending, mirrored maze of yellow-wallpapered, yellow-carpeted interconnected hallway spaces lit by loudly humming fluorescent lights. This is the whole piece. The time’s youngsters couldn’t get enough of it. It spoke to them. They looked at the infinite yellow maze with a fascination, as if it were a recreation of somewhere they had seen in a dream. Hand-in-hand with it came a contextual backdrop of refreshed interest in the psychological concept of liminality, defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as an adjective applicable to something “between or belonging to two different places or states.” Various voices from architecture, psychology and art theory have been keen to have a go at grasping just what it is about it that allures. Writing on liminality has made reference to it as “…emotional, conveying a sense of nostalgia, lostness, uncertainty”, “…lacking activity or purpose, unused or in transition, connecting to a basic human condition of ephemerality”, and “…dream-like, a way of remembering the past or exploring the condition of time passing though impossible to locate, thus transcending time and space eerily.” We have it there. This was the new reference point for exoticism for the first generation to come of age in the twenty-first century. The nostalgic liminal space, striking the curious balance between the familiar and the unfamiliar, existing half-inside, half-outside of the monotonous everyday passage of time and space. It tugs at something.

In this reality, out of left field: Britain is suddenly as exotic as the South Pacific or the great works of pre-war science fiction once were. To fully understand the allure of that beyond the fences of this particular island, one must understand Britain, with an added emphasis on her artificial fabric. The true potential enrichment which UE can impart requires this bond, as a sculptor must understand the properties of his clay or his bronze. A senior industrial society comprising a crowded, numb, predominantly ugly and dull peoples – for whom paying some of the world’s highest tax rates in return for some of its most cumbersome basic services is just par for the course, habiting hospital waiting rooms night and day for minor ailments is something of a national sport, and Friday afternoons are spent sitting for hours in standstill motorway traffic – placated by the banal yet unable to be astonished by much, cards close to their chests but forever nosey and judgemental about whatever crosses their path; British people purport to love fun, quirks, spectacles and amazement, but in reality what they love an awful lot more is order. The self-proclaimed maxim that the British detest ‘being told what to do’ could not be more spurious. Rules made Britain, rules maintain her, and rules have a noose round her neck. They command such deep respect here that the overgrown jungle of bureaucracy dictating every iota of how the state operates has become so suffocating that it will eventually, perhaps soon, crumble society into a mess. In Britain, there is no escape from rules. She has made her greatest strides of progress smothered under the sturdy frame of order and procedure; in her imperial ambition, industrial prowess, commercial proficiency. Everything methodological, diligent, decreed. In moments in British history where there has been a threat of erosion to procedural rigour and diligence one can see a nation flustered and itchy for a brief instance; the World Wars, economic downturn and high unemployment, generational blots of civil unrest. The rules soon return and prevail: a default reversion, everyone is comfortable again. The urban explorer pursuing as great an immersion as possible in his own little world must understand this triangular dynamic between Britain, her deep love for her rules, and an attempt to introduce a dearth to the latter.

Amidst thriving rules and procedures, Britain built. One cannot remotely overstate what a triumphant, breathtaking and prodigious array of objects Britain has built, in as much of a response to the phenomena of the time as a testament to her engineering capabilities. Britain wanted fine sartorial luxury, so she built textile mills and towering chimneys spanning entire river valleys. When wool was not merely enough and a cheaper synthetic material was what was needed: Britain built the Terylene factory at Wilton, just like that. Britain decided to build three-dozen sprawling psychiatric hospitals out of stone and granite to house those who she deemed her ill-minded, then decided to build three-dozen more. Her capital had become congested and her cross-country railway network hemmed in by hilly upland, so Britain bored hundreds of miles of train tunnels to ease the logistics. After almost perfecting the process at the first time of asking in eighteenth-century Sheffield, Britain sought more steel – so she clicked her fingers and works the sizes of large towns from the South Welsh valleys to the pastures of Lincolnshire appeared. With this steel Britain built a nationwide electricity grid and the supply to go with it; endless power stations, their cooling towers rising higher than the skylines of most of her cities, their inner systems as intricate as something biological. Britain built aircraft that changed the course of world history, dammed hundreds of reservoirs to manage her water supply, stuck a colliery in every patch of every coal field, fastened ships to circumnavigate all oceans on the banks of the Tyne and the Clyde, wired telecommunications which foresaw the imminent future of the skies. Then, Britain got spooked that all of this might soon be no more, so she burrowed into the ground; under common or garden pastoral realms in her unassuming hinterlands or into the bedrock below her cities to create a mirror of somewhere – some kind of accommodation – where a slither of her people could hope to cling on to the last straws of law and order that could possibly endure the end of the world. Britain was a titan of the structural, a ready and willing martyr for the rule-based order through which she built herself.

Past tense. For all that: this myriad is already far beyond a generational cycle in age. Ergo redundant. Everything of a utilitarian purpose Britain builds with her rules, she will attach more onto: all structural entities here that work towards something, produce something physical, house something institutional – they all must have a life expectancy. When you look at Britain, you are looking at a civilisation that has not only in all social and cultural respects been on a trajectory of out and out disintegration for at the very least a fifty year timescale, but in structural respects as well. In every direction a precocious, prodigious and prolific industrial society is shedding its skin like a reptile, leaving a trail of exuviae across the hills, fields, coastlines and cities from Land’s End to John O’Groats. The glut of structural Britain which has shed its skin presents an onslaught of curiosity that will come to infatuate the urban explorer, yet will only flirt with the average Briton. For to interact with this exuviae intimately, one must first disregard her fences and what they stand for. This demands compulsion. Illustrator and amateur writer Nick Hayes correctly points out in his popular non-fiction book The Book of Trespass, a playful modern examination of land ownership in Britain, that “to step over the line into private property is, in the eyes of the law, not an act of digression but of aggression, and makes the landowner the victim. […] The first act of violence is the trespass.”

The notion of the fence, the embodiment of the rule of private property: this is something Britain is oh so fond of. It is an equilibrium. On such a crowded island, an unwavering corner of personal space is a core component in the backbone of cultural life. The fence is a reassurance to Britain, it asks the delinquent what on earth he thinks he’s doing, shuns him by its idea alone. The fence is the manifestation of a deep-rooted order, and to climb it is thus to launch a little attack on the very societal fibre of Britain. The urban explorer can be identified by possessing a vision of something beyond the fence, of something greater than this defiance, that the average Briton cannot see. A kind of romance.

With a promise of the romantic and the exotic hand in hand, the urban explorer stares at the fence pensively. But he is not yet climbing it. He needs to be promised one more component before he physically grabs it, begins to strain with it. Because like all theatregoers, sports fans in a stadium, tourists at the seven wonders of the world: he is a simple creature too. He is of course after a spectacle. He wants to look at something beyond the fence which will impart upon him a profound sense of awe – that will subdue him into a gleeful submission by something larger in every respect of emotion than him in its individual parts or the sum of them. He wants something stunning in his presence.

And so if there is spectacle, there is romance, and there is exoticism; there is the lifeblood of reward for the urban explorer. This can be referred to as epic. A pursuit of epic – this tripartite currency – is what defines the persona of the urban explorer, and what sets him apart from the often overlooked array of other parties who may find themselves in the same arenas he concerns himself with, in ROADS; staff, demolition workers, vandals, thieves, graffiti writers, squatters, drone pilots, pirate radio broadcasters, grow-oppers, BASE jumpers and other extreme sport practitioners, activists, terrorists. This is probably an incomplete list. For them all, such a place is of a serviceable value. A means to an end. For the urban explorer, the place is the end to a means.

Broad UE scenes have thus grown to noteworthy extents in predictable corners of the world at a similar rate. Those corners where things of great ambition were made, and since when enough drastic socio-economic shift has elapsed that these things have seen themselves decidedly un-made. In Europe, in Anglo North America and Australia; the great steering committee of the modern global economy, for whom the structural and mechanical was the pivotal stepping stone to this end – and in the former Soviet Union; where millions, tens of millions of souls perished miserably for the cause of the industrial and technological from Lviv to Anadyr. A nascent Shanghainese scene has even emerged as China’s industrialisation pushes into a next generation. The Japanese urban explorer, where the man-made environment offers him all the things he is looking for also, is a far more elusive sighting, though he is due his moment any day now. For the agrarian and the tropical world; the very recently industrialised world and the world in poverty? UE is not a concept, does not compute yet.

In light of this umbrella of UE interest transcending borders, all sharing a denominator in environment, vision, attraction, is it reasonable to ask: just what constitutes worth of epic, a motive of positive output to the urban explorer? Unanswerable straightforwardly I’m afraid. Every variation one can imagine. For some, it’s about aesthetic; about how luxuriously the epic treats their lens, the strictly photographic subject matter of what can be seen here or there as commodity. Emphasis on the spectacle. Others: purely curious in the way an historian is – about what kind of stories mouldy paperwork tucked away in managers’ offices of crumbling factories for redundant manufacturing might tell, what trinkets lie discarded around this corner or behind that door, how they can get inside the head of the architect long passed and see his decision making in real time. Emphasis on the romantic. Some enjoy a chance to get up close and personal with the physical merits of a range of different structures wholly at an arm’s length from the rest of society; to experience what it’s like to be amidst assorted alien utility and liminality. Emphasis on the exotic.

Others believe it is the only way to truly and comprehensively get to know where they live; they feel obliged to trespass in order to learn about their local environment, to know what the perspective on things is from behind the dilapidated shopfront or from atop the shopping centre roof – they seek to know how they can reach a point in their environment if they move this puzzle piece here and that one there. Emphasis, one might say, on ‘exploration’, demonstrably. The rare stamp, too, entices further collectors to play, to flesh out their books. Some are motivated and buoyed solely by the desire to discover; to unturf something previously unknown to their peers, to break ground, to report back from purely the frontline, whilst fewer still are possessed by the idea of the technical challenge; of pulling off the perfect heist, of venturing over fences not dared scaled before in search of a hitchless, clean and invisible trespass experience using techniques others would not have the patience, knowledge or vision for. Both of these, commendably: emphasis on exclusivity and originality in a world of monkeys seeing and monkeys doing.

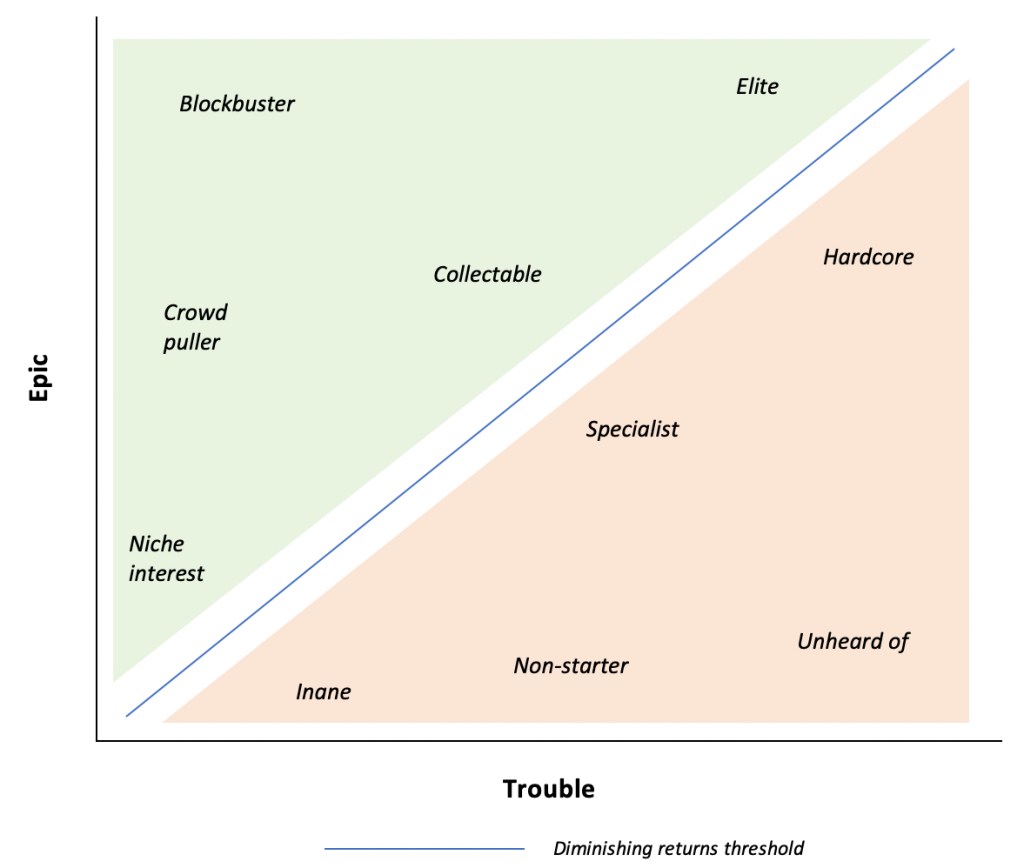

The latter character, especially, embodies the fact that there are no places; no epic for the urban explorer, without inputs. A bit of work. Sometimes the work is easy, quick; sometimes it’s harder, longer. In this regard what makes the practice of UE so much of a game, so much of a gratifying and addictive chase, is the tenuous existence of a loose correlation between the potential magnitude of the epic on the table and the concept of a ‘difficulty’ of trespass. The chance for a practitioner to pursue to some degree a specialisation, a refinement of expertise and experience in the technical practice of trespassing to seek bespoke reward in a gradually harder hit of the very reason he decided to undertake his very first bit of UE. Whilst the graph is not a neat and tidy one, I’m sure that the statistician would not shy away from pointing out a correlation.

The parameters of inputs are the more complex, myriad; concerning identification, exertion, application. Parameters of vision, effort, difficulty and danger are all to be considered. Am I any good at identifying where deposits of epic may lie on a map of every square foot of my country, and how exactly do I need to travel to uncover them? For how long, how intensely must I focus entirely on undertaking the UE task from beginning to end? Will it require an action or several of a varying level of capability: a challenging climb by any standard, use of a rope to work at height, circumnavigating an obstacle in a creative way that may cross the mind of only certain players with a certain criteria of experience bestowed to them, a perceptional awareness of a situation which could only allow for the eagle-eyed to proceed? Will my safety at one moment or several come down to my proficiency at placing my feet or hands onto precise points of a ladder, the ground, a piece of metal? Inputs arrange themselves for the individual like a collage, a scatter graph.

Outputs meanwhile are a simple yin and yang, x equals y. A bespoke blend of epic sits at one end of the output spectrum, but on the other sits the reason for the hobby’s acquired taste, rogue image, its underground profile, why one may find many prospective interest-takers hesitant to buy in and put boots on the ground. This is trouble. Trouble is a deciding, encompassing, vital force of nature in all of UE. Part and parcel; creator of the parameters of the activity as much as epic can be considered the driver of performance and artistry therein. Trouble is a limitless gradient of grey; inferable, assumable from afar, but seldom quantifiable until it imposes itself.

When thinking about UE from a distance it’s easy to forget that it’s not what one is meant to do, though when in the middle of it, forgetting is a lot more challenging. Trouble exists by virtue of the kind of artificial locality appealing to the urban explorer being in black and white legal terms private property, backed up by a strong aforementioned culture of considering unsolicited, delinquent interference with it taboo, an affront. Cambridge economist Joan Robinson notes in her 1962 Economic Philosophy essays that “in the absence of respect for property it would have been quite impossible to achieve a reasonable standard of life. […] The happiness of society depends on such virtue.” The end result of an outcome involving trouble is distinctly social; trouble is at its simplest a comeuppance, an equalising reaction by a person or group of people who hold legal jurisdiction over the locality in question – always referred to as ‘they’, their existence and function completely impersonal – to incur a level of inconvenience either proportionate or disproportionate to the inconvenience they might feel one’s decision to trespass has caused them.

Shades of grey start to take on tone. Here is separated the level of trouble able to be encountered in and thus associated with, say, a derelict building versus critical national infrastructure; agricultural pasture versus varying forms of military land, suburban brownfield wasteland versus railways, building sites versus demolition sites, and everything in between. Trouble can manifest as anything from civilly drawing curtains over an exploration of somewhere prematurely to being life changing. The potential of trouble is tautological to UE, and at the very least an effort towards its evasion, if not for the circumstances mandatory, is a core clause of the contract when signing up to take part in it. If it were not for trouble, anyone could just stroll into anywhere without anything happening, and there is simply no point in any of this.

Nobody wants trouble. Nobody wants the tedium and stress of it, awkward confrontation or serious frenzy alike. Many fear it, its potential repercussions. Others feel as an outcome that it means a failure of the whole point of their undertaking; a payment withholding on the grounds of inadequate performance, a forced surrender of any high of accomplishment and epic the exploration conditionally promised. Trouble goes to one’s head, is really able to affect an individual’s internal chemical ebbs and flows whether he likes it or not, and deeply influences motivations and approaches. It is statistically when a thoughtfulness and adeptness beyond the standard call of duty is demanded in evading potentially serious trouble for the pursuit of outstanding and exclusive epic where UE gets particularly interesting, worthy of remark, and sees the number of players dwindle.

The equation for any earnest trespasser’s assessment of mitigating trouble takes into account how much of it his prospective undertaking could result in deducted by the likelihood of it coming to pass. This is easier than one might think to get a sense of by asking sensible questions. What is, or what was the function of where I’m looking at trespassing? Who – what entity or what individual – holds stake in this function? A bloke? Some blokes? A landowning entity with tenuous degrees of interest? Or a multinational organisation for which where I’m looking at forms a central part of their asset portfolio? Okay, the next round of queries: time to get to know who or what has the stakeholder delegated to secure their property. Are they machine, or human? Through what interface is trouble going to seek me, the trespasser, out? Will machines – sensors, cameras, alarms – summon an outside party on an arbitrary trip system, or will a different kind of human, one in-house, take it upon himself to bring trouble to me?

And we follow the flow diagram to the next bifurcation, on to the next round: how can I get to know this guy without him getting to know me? For trouble to come to me, in this place, with a human in control of how it is administered, will require action; movement, exertion, an operation. So let’s posit: how much does the man being paid to securitise the place value his job, how much vitality is there to his sense of duty? Has he been asked to sit half of his shift in a hut with the radio on smoking tabs and the other half scrolling Facebook in a van with an open tailgate and a dog, protecting a derelict building whose owners are far away offshore and pay him meagrely? Or, on the other hand, does making his family’s ends meet rely on him performing exceptionally against key performance indexes including but not limited to ensuring zero instances of theft, trespass or activism on the site? The bottom line one is trying to find out from this preliminary inquisition is simple: how sinister, how much of a scumbag am I going to look like if I find myself in trouble, and what does this mean for me?

All this therefore dictates that the British urban explorer with anything to lose bumps his head on a glass ceiling when he meets with a document known formally as Home Office circular 018 / 2007: Trespass on protected sites – sections 128-131 of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. In it one can find a list of sixty specific sites in the United Kingdom deemed by Westminster to so crucially need a total absence of the trespasser as for his presence to become punishable by a prison sentence. The list of sixty is thematic; the scope of the sites without fail can be categorised fourfold as those pertinent to the Royal Family, the handling of any fissile material in civil or military capacity both formerly and currently, high profile governmental workplaces, and to a presence of the United States Air Force or strategic trans-Atlantic military cooperation. A decommissioned miniature fission reactor site at an Imperial College campus no bigger than a bouncy castle, burglary on most of Whitehall, the other side of the odd door not forming part of the demarcated public tour through the Sandringham Estate, and RAF bases across the East of England just like any others which just happen to have a few bits of American airbourne hardware parked up on the apron, share the same company. The astute reader may find a few omissions surprising, such as the Animal and Plant Health Agency – where open vials of swine flu and foot-and-mouth sit overnight – or Madley earth satellite ground station – where a good deal of the nation’s radio wave telecommunication and broadcast links are tethered to – but to the national security scholar I’m sure the list feels sensible and thorough without giving an air of a police state having drafted it.

Who doesn’t like a challenge?! On a dark winter’s night in a rural field, a trespasser detonates a transient electromagnetic disturbance device he acquired on the Dark Web. It knocks out the power to an electric fence and infra-red camera system surrounding a military base where weapons of mass destruction are manufactured. After the power is out, the man scales the fence, touching down onto an open expanse between it and the site perimeter road. Military trucks pass, frenzied by the power outage, and the man drops to the ground disguised in a ghillie suit. His target is to reach the site’s central containment facility. Outside the main gate of the base, he has hired some goons to cause a raucous by doing doughnuts with their cars. Main gate security is focused on this distraction whilst he makes his way deeper into the base. Reaching the building in which the containment facility is located, an armed guard stands outside its doorway. He gently creeps up behind the guard and puts a chloroform-covered cloth to his face. Inside the building, he avoids several more military personnel by ducking into corridors – he is able to do this because he has a sonar-tracking system installed illicitly on his smartphone courtesy of a contact in the intelligence services, and is thus able to see where personnel are moving in the building before their paths are crossed. Armed police and police helicopters soon arrive at the scene, the latter equipped with infra-red cameras, but as the man is wearing a tin foil-coated costume under his ghillie suit, he is invisible to the ‘eye in the sky’. At the blast door to the containment facility, cameras pointed at it still without power, he begins to cut through with a gas axe. Soon, the facility is breached, before the man is able to make his escape to conclude a daring act of UE.

Guess what? This didn’t happen. None of this happened, nor will ever happen. This is total fantasy. It is so far beyond the mandate of the mere hobbyist that it is hilarious to think any reader believed they were looking at a true account. Yet if accounts the urban explorer has to offer do not make for remotely rousing reading; if he does not dice a little with a form of adversary, get his hands dirty poking the bear, pull off a stunt or two to get a gasp from the audience, then why bother to write about it? Why drag the clichés of beautiful ruination and clement rebelliousness through the mud, talk straight at a half asleep listener about what he pointed his digital camera at on a Sunday walk?

And so here we can see the nether zone that the ambitious explorer inhabits; lost, confused and a laughing stock somewhere between Hollywood secret agent and quirky tourist-come-metal detectorist. There are limits to his endeavours within the confines of basic realities, measured reason, personal prudence, yet he must disregard these at least somewhat, to a confusing degree, in order to achieve anything; progress a discipline, conquer any special feats, garner tales or insights worth putting to paper. Perhaps this sets a tone for why writing about what they get up to, and what they think about what they get up to, has proved one of the biggest challenges for its practitioners over the years once they returns home and puts their feet up. When one writes about UE, there are four categories of rut one carves out and pigeonholes oneself in on the way to sounding either a bore or a loon.

The UE author in the first rut deals strictly in reference non-fiction about artefacts alone, and attaches no frills to his work. He says: look at these places that I am visiting, documenting, and learn about them through my doing so which the man in his office cannot. Look at what they used to do, how they were designed, operated; look at their fine details through my lens. Me? Doesn’t matter how I feel or how I got here – this is the place and we’re here. Here are the facts as follows about the place.

The second propounds an artistic concern, and asks the reader to revel with him, for a moment, at how amazing it is that these objects built by man are left like they are, that this is what happens to his structural follies after him; they decay like this, they are shrouded like this, that this is what it looks like when humanity locks up and moves on. And how it is only people like the author who can show you! Isn’t it wondrous how there is such emotion in the forgotten, and such scope for artistry therein?

The third is a memoirist, a raconteur if he’s any good. Grab a drink, sit down. Get a load of this: this time that we went here. This place? You wouldn’t have heard about it, but this wasn’t any walk in the park. All this was required to go here; all that action happened, panned out in such a way. It might be hard to believe, but this is what we do!

And finally the fourth rut: the author in there is grabbed by the idea of what the hobby means for the examination of human conditions. Isn’t it remarkable how there is this little-known community of people who disregard deeply ingrained cultural confines and challenge imposed borders around them? Is this not a phenomenon of cultural and sociological note? How fruitful an alternative a lifestyle this could behold, too – what opportunities!

Martin Dodge, professor of human geography at Manchester University, noted in a 2006 lecture on the then-emerging UE practice – one of the first and only of its kind to make a rogue appearance in academia – that those partaking are hallmarked by the shared ideals of: a need to document space, a desire for authentic spaces and alternative aestheticism of spaces, and a thrill of access to forbidden space. That’s ruts one through three. Rut four? That’s the man himself speaking.

There is really no way around it, there is no choice but to mix them all. And what do you know? Whichever way he spins it, the urban explorer is to be second best; back in his confused nether zone. In his pursuit to be today’s incarnation of the explorer of new frontiers, to tread where no one else has since the parameters of his game began; he is more consistently outclassed by the likes of the speleologist, the cave diver, the wreck diver, the deep oceanographer and the mountaineer. Upon striving to accrue the wealth of a storyteller, to obtain extravagant tales to recount from an apex of excitement and feat, he is drowned out by the likes of the special operations soldier, the mountaineer again, the spy, the gonzo journalist hot on the tail of guerilla conflict deep in the truly wild parts of the world like Ryszard. In his own little quest for a sense of accomplishment, to offer something of interest, entertainment or worth others can’t to the wide world, he is an afterthought, barely in the runnings to be taken seriously; surpassed left right and centre by professionals of medicine, engineering, athletics, music. As a protester he is irrelevant and lukewarm, as a formal archaeologist an outcast, as a sociologist wacky and forgettable. Stripped bare, the cynic pins him as just another self-indulged nuisance.